Bully Boy Distillers

Running along one wall of the Bully Boy distillery is a shelf that holds a collection of dusty, empty liquor bottles.

The labels – faded, smudged, and grimy – advertise dubious contents such as “Very Old Cow Whiskey” and “Pale Brandy.” A “Fine Old Medford Rum” looks anything but fine, though it’s definitely old. Even familiar brands like “Bacardi Rum” are a little suspicious when their names are typed onto ordinary household labels.

A closer examination of those labels – particularly the dates, which stretch back to the 1920s and 1930s – reveals why the names are so unusual and the contents so questionable. This was bootleg liquor. In an era when Prohibition is endlessly glamorized and so many bars try to recreate the experience of drinking in a speakeasy, these bottles are the real thing – a tangible, authentic connection to a period of American history that mystifies and fascinates us to this day.

But to brothers Will and Dave Willis, owners of Bully Boy Distillers, the bottles are more than just artifacts. You might say they’re family heirlooms. The bottles once belonged to the Willises’ great-grandfather, who locked them away in a vault on the family’s farm in Sherborn, Massachusetts.

Will and Dave discovered the vault in the basement of their farmhouse when they were kids, but it would be some time before they appreciated the significance of their find. And while there’s no evidence that their great-grandfather had any role in making the hooch, there’s little question that his farm was the place to be back when booze was banned.

“On a lot of the bottles, our great-grandfather would write all the names of people who were at the drinking session,” Dave tells me during a tour of his Roxbury distillery. “It’s incredible, all these old signatures on the label from the 1920s and earlier. It’s a nice tie-in with where we came from and what we’re doing here.”

What they’re doing is making a line of small-batch spirits that have fed consumers’ demand for artisanal liquor and given bartenders a slew of unique options for creating innovative cocktails. Bully Boy Distillers opened their doors in 2011, the first legal craft distillery to set up shop in Boston in decades.

Four years later, Bully Boy is one of the most recognizable liquor brands in the city. Their spirits have become go-to options at a host of local establishments and are integral to any number of signature cocktails.

And while their distribution is presently limited to Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and New Hampshire, their growing product line has garnered recognition and praise from across the country – at the front of the distillery is a shelf full of bottles adorned with gold, silver, and bronze medals won in numerous national spirit competitions.

Those award-winning spirits are situated just a few yards from the old bootleg bottles, and while they’re oceans apart in terms of quality, it’s not difficult to discern a connection. Growing up on that same Sherborn farm, the Willis brothers experimented with making hard cider before learning the finer points of distillation – using a five-gallon stovetop still.

And despite the success they’ve enjoyed in their first four years as professional distillers, the Bully Boy operation remains small in scale, with Will and Dave toiling under fairly harsh conditions.

Their utilitarian distillery is in a nondescript warehouse that you won’t find without a reliable GPS unit. Inside are the tools of the trade, and little more – a 150-gallon still, fermenters, storage containers, empty bottles waiting to be filled, and a room with rows and rows of oak barrels. In the summer months, temperatures in the distillery can soar to 120 degrees.

“It is so hot in here, which is brutal,” Dave wearily acknowledges. “Obviously you sweat all day long. It’s a really tough environment to work in, but it’s awesome for aging, because the barrels swell.”

Pointing to the barrels, he notes that small quantities of spirit and sap can be seen oozing out of the seams, and he explains the benefits of that presumably sticky process.

“The wood really expands when it heats up,” he says. “And then the spirit inside the barrel also expands and pushes up through the wood. It extracts all sorts of wonderful flavors and aromas from the barrel, and in the winter the barrel contracts when it gets colder.”

Bully Boy uses each of its barrels twice – first for their American Straight Whiskey, then for their Boston Rum. And while the aging process may seem fairly straightforward, Dave explains that there’s more to it than most people know.

“Barrel aging is one of these really mysterious things that treatises are written on,” he claims. “And the wonderful thing about it is, there’s a lot about barrel aging that no one has an answer to. So it’s kind of this cool, mythical part of the whiskey making and rum production process.”

After a short lesson on barrels, Dave walks us through the distillation process, from mash tun to fermenter to still, and ultimately, to barrel or bottle. I won’t even try to explain the process in the detail that Dave can, but the tour is entertaining and informative.

After that, it’s time to sample the goods. Bully Boy currently offers six products, each made with locally sourced ingredients whenever possible, including Boston water.

Vodka

The tasting begins with their vodka. Using red wheat as a base, the vodka is clean and bracing, with a hint of sweetness, but no burn whatsoever.

White Rum

Made with blackstrap molasses, Bully Boy White Rum is less sweet and more robust than typical white rums, with a distinct fruitiness. Dave explains that white rums have historically gotten a bad rap because of a certain large rum distillery that dominates the global market with a product that’s largely flavor-neutral.

“We tried to create a white rum that has more to it,” he says. “There’s no point in coming out with another neutral, molasses-based white rum. If you’re going to do a white rum, or any spirit, you want to do something that’s got some uniqueness to it.”

White Whiskey

And on that note, Bully Boy’s white whiskey may be their most notable contribution to the world of spirits. Unaged whiskies had been steadily growing in number and popularity around the time Bully Boy started selling theirs, but most distillers seemed more interested in efficiency than quality. Not having to age the whiskey means saving money and time, and while some producers made quality white whiskies, others just ratcheted up the novelty factor (think corn whiskey and “moonshine” sold in mason jars).

Dave explains that the key to making a good white whiskey is treating the spirit differently than one intended for aging.

“The mistake that a lot of people make with unaged whiskey is they simply take the stuff that they would put in a barrel and they stick it in a bottle,” he says. “If you’re not going to get the benefit of the barrel, you’ve got to create the cleanliness through the distillation process and the choice of grain.”

Bully Boy uses wheat for its white whiskey, which is fruitier and more subtle than the typical corn base, and distills the spirit at a higher proof. The result is a clean flavor that pulls from several spirit types, like tequila, gin, and grappa, but still has the graininess of whiskey.

While it can be enjoyed neat or on the rocks, Dave thinks of the unaged product as a cocktail whiskey. “There are cocktails you can make with unaged whiskey that you cannot make with any other spirit, so again it’s really adding something to the world of spirits,” he says.

American Straight Whiskey

Bully Boy’s American Straight Whiskey, on the other hand, is made with sipping in mind. Aged in American oak barrels, the whiskey’s blend of grains – corn, rye, and malted barley – give it a balanced flavor, with a bourbon-like sweetness up front and spicy rye notes in the back.

Boston Rum

Bully Boy’s other aged product, Boston Rum, hearkens back to Boston’s pre-Prohibition glory days as a center of rum distillation. Made with blackstrap molasses, it’s lighter and fruitier than typical dark rums, which often have caramel coloring and sugar added to them. The barrel aging contributes some complexity but doesn’t overwhelm the flavor.

Hub Punch

Finally, the Willis brothers again demonstrate their appreciation for history with one of their more unusual products. Hub Punch is inspired by a recipe that was popular in Boston in the 19th century but slipped into obscurity during Prohibition.

Mimicking the lost formula, Bully Boy infuses their Boston Rum with fruits and botanicals for an herbal, fruity spirit, with understated notes of tea and licorice. Dave says it’s best in cocktails, which is how our local forebears apparently consumed it. Mixed with ginger ale, soda water, and lemon, the Hub Punch cocktail is a portal back to Boston drinking culture in the years leading up to Prohibition.

The Hub Punch is only the most recent instance of regional history informing Bully Boy’s otherwise modern craft. Even the company name ties back to the family farm. Will and Dave’s great-grandfather named his favorite workhorse “Bully Boy” after a phrase coined by his college roommate – future U.S. president Theodore Roosevelt.

And then, of course, there’s that vault of timeworn bootleg liquor. I can’t resist asking Dave my most burning question – has he ever sampled his great-grandfather’s stash? He replies in the negative, explaining that the bottles are in even worse condition than they appear. Most of the corks have degraded and, if you look closely, you can see a layer of sludge at the bottom of the bottles.

But by the tone of his voice, I can tell he’s considered it. The contents would certainly be disgusting, and possibly even toxic. And yet, just one sip would be like going back in time. How many people alive today have tried that stuff?

“I’ve been tempted,” he concedes. “But….I have two kids now, and uhh…”

Fair enough. And despite Will and Dave’s ties to the past, their future is much more pressing. Next spring they’ll release their first gin, and a wheated bourbon is a few years away.

They’re also moving on up – later this year, they’ll be leaving their current distillery for a new, larger facility with more advanced equipment and a tasting room that will overlook the production floor. Dave becomes particularly animated when talking about Bully Boy’s future home, promising it will be a major upgrade from the current environment.

And a very long way from a stovetop in their family farmhouse.

Address: 35 Cedric Street, Boston

Website: www.bullyboydistillers.com

* * * * * * * * * * * * *

Copyright © Boston BarHopper. All Rights Reserved.

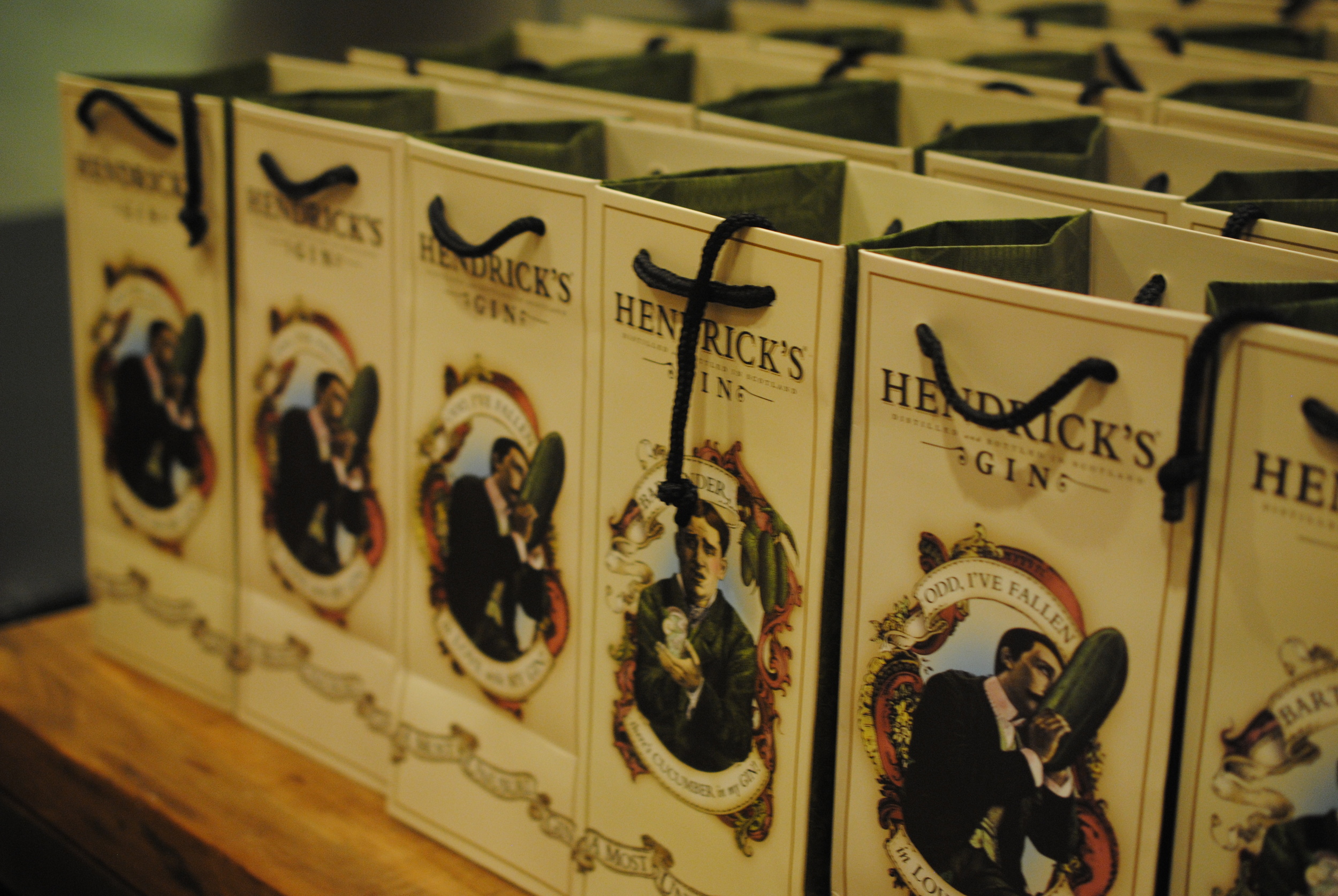

Tanqueray Bloomsbury

If you’re a gin drinker, this is a good time to be alive. Not only has the herbal spirit enjoyed a global surge in popularity in recent years, but the advent of craft distilling has introduced a stunning array of small-batch gins to the market. With so many products to choose from, it’s almost hard to remember the time when our choices were limited to just a handful of major labels. Of course, those long-established brands still dominate the market, unthreatened by the multitude of tiny upstarts. But some of the big guys seem to have taken notice of gin drinkers’ evolving tastes. Gordon’s gin, one of the oldest gins in the world and still the best selling, in recent years introduced a cucumber gin and an elderflower gin. Another titan, Beefeater, began offering a barrel-aged gin a couple of years ago.

And then there’s Tanqueray – the sexiest of traditional London dry gins and the subject of this week’s post.

With roots dating back to the early 19th century, Tanqueray is among the oldest and most renowned gin brands on the planet. I’ve always found it to be the most alluring, as well. Something about that iconic green bottle, with its waxy red seal, commands respect as it evokes a sense of mystery.

As timeless as Tanqueray London Dry may be, the brand remains open to a little experimentation. The venerable distiller has debuted a series of limited-release gins in the past few years, beginning with Tanqueray Malacca, a spiced gin, in 2013. Tanqueray Old Tom followed a year later. And just last month, the gin distiller unveiled its newest variation – Tanqueray Bloomsbury.

It’s not quite accurate to call Bloomsbury “new.” The gin draws its inspiration from a recipe by Charles Waugh Tanqueray, son of founder Charles Tanqueray, that dates back to 1880. The name derives from Bloomsbury, England, the London district that the Tanqueray distillery once called home. Whereas Tanqueray’s London Dry employs four botanicals in its recipe, Bloomsbury uses five – a special “Tuscan juniper,” angelica, coriander, winter savoury, and cassia bark.

Before I tried the new variation, several people remarked to me that Tanqueray Bloomsbury is “very juniper-forward” – a characterization I found somewhat amusing. The juniper berry is what gives gin its distinctive, pine-like flavor, and that quality is prominent in all English gins. So describing Bloomsbury as “juniper forward” seems kind of like describing a steak sandwich as “meat forward.” But I got a chance to try it out for myself this past week, when brand ambassador Rachel Ford – affectionately known as Lady Tanqueray – stopped by the Sinclair in Harvard Square to show off the Bloomsbury and demonstrate its versatility in cocktails.

The event was marked by the elegance you might expect of such a classic English brand – candles and bouquets of flowers adorned the tables at the Sinclair, and soft lighting set the mood for sipping gin and indulging in easy conversation. The featured spirit was available for sampling, and given the way the Bloomsbury was described to me, I was expecting an intense blast of juniper. Yet I found it to be surprisingly soft and wonderfully floral. It’s definitely juniper-forward, but the botanicals are well balanced, with notes of spice and, less prominently, licorice. It differs noticeably from the London Dry but clearly remains within the Tanqueray family in terms of style and overall flavor profile.

With that established, it was time to see how the Bloomsbury fared in cocktails. And why not start with the most iconic of gin drinks? The Bloomsbury Martini featured the specialty gin, dry vermouth, and your choice of olive or lemon (mine is always the latter). This traditional cocktail truly showcased the Bloomsbury, with vibrant notes of juniper and just enough dryness to make it a bracing, slow-sipping drink.

The Satisfaction lived up to its name. This bold cocktail combined Bloomsbury, cranberry, cucumber, ginger liqueur, and lime. It was an impressive mix of flavors that were expertly balanced, making for a smooth, refreshing drink.

The Ramble On, meanwhile, was simpler in composition but surprisingly complex in its flavor. A mix of Bloomsbury, Becherovka, agave, and lemon, a prominent cinnamon flavor accompanied the floral notes of the gin in this sour drink.

Tanqueray has been making gin for nearly two centuries and remains a market leader to this day. The brand has no need to reinvent itself. But as the gin market gets more crowded and new voices join the conversation, Tanqueray’s occasional product diversification is a way to engage new audiences and capitalize on our evolving definition of what constitutes an outstanding gin. And by revisiting one of its own recipes instead of chasing the latest trends, Tanqueray demonstrates that its brand can be traditional and dynamic at the same time.

* * * * * * * * * * * * *

Copyright © Boston BarHopper. All Rights Reserved.

Glendalough Distillery and the Independent Spirit

Ireland’s history of distillation is as turbulent as it is long.

At its height of production in the 18th and 19th centuries, the small island boasted 200 licensed distilleries and perhaps as many as 2,000 illicit ones. But heavy taxation, regulation, two world wars, and the loss of a certain large customer due to Prohibition brought the industry to its knees, leaving only a handful of distilleries in operation to this day.

Loss of Independence – and Identity

Most of the remaining distilleries have ensured their survival by allowing themselves to be purchased by multinational conglomerates with multiple brands under their respective umbrellas.

That bittersweet progression reached a culmination of sorts in January 2012, when the last independently owned whiskey distillery in Ireland passed into foreign hands.

Now in one sense, this isn’t all bad news. Deep-pocketed corporations pouring money into a domestic brand can create or sustain jobs, modernize aging facilities, and open up new markets in far-flung regions.

But for a nation that cherishes its independence the way Ireland does, it must be galling to know that some of its most beloved products amount to little more than a line item on some foreign company’s balance sheet.

And while Irish whiskey has enjoyed an international renaissance in the past five years, there’s something perverse about Bushmills whiskey being owned by Jose Cuervo.

The Return of Craft

But Donal O’Gallachoir is helping bring Irish distillation back to its roots. Donal is one of the founders and owners of Glendalough Distillery – the first craft distillery in Ireland.

Founded in 2011 as the brainchild of five friends from Dublin and Wicklow, Glendalough Distillery represents an effort to recapture the character and heritage of a centuries-old industry that’s had more than its share of ups and downs.

“We wanted to bring back something real, something historic,” Donal tells me over drinks at Fort Point’s Blue Dragon. Glendalough’s brand manager, Donal relocated to Boston last year and has been bringing the distillery’s growing line of spirits to American shores.

And while Glendalough is a young distillery, Donal and company have cloaked their brand in Irish history, from basing their spirits on ancient recipes and methods to adopting the figure of St. Kevin, a 6th century Irish abbot, as something of a spiritual guide.

The Legend of Kevin

While from a distance it might look like Gandalf preparing to take down a balrog, that’s St. Kevin on the label of Glendalough’s bottles. The founder of Glendalough, the beautiful valley in Ireland from which the distillery takes its name, St. Kevin is known to have been a fiercely independent holy man, though the actual record of his life is long on folklore and short on verifiable facts.

The most enduring legend involving St. Kevin, immortalized in verse by the late Nobel Prize-winning Irish poet Seamus Heaney, is that a blackbird once landed in his outstretched hand, and such was Kevin’s patience that he remained completely still for weeks while the bird built a nest and laid eggs, not moving until the chicks eventually hatched and flew off.

The blackbird story is an allegory of determination and independence, and it’s easy to see why a fledgling distillery would draw inspiration from the celebrated saint.

Those characteristics are evident as Glendalough continues its gradual rollout. The product line is small but growing, consisting of three aged whiskies, a gin, and a spirit that relatively few Americans may be familiar with – poitín.

Irish Moonshine

Poitín (pronounced put-cheen) represents a fascinating chapter of Irish history and culture. A spirit traditionally made from malted barley, sugar beets, and potatoes in a pot still, poitín predates whiskey and is considered one of the oldest distilled beverages in the world, first appearing in written record in 584 A.D. Irish authorities prohibited its distillation in the 17th century, but production continued in secret, making it the Irish equivalent of moonshine.

And once it retreated to the shadows, poitín became the stuff of legend, with an alcohol content ranging from 50% to as high as 95%. After 300 years of illicit production, poitín was approved for exportation in 1989 and finally for domestic sales in 1997.

Poitín’s historical credentials make it an entirely appropriate product for a distillery trying to recapture the essence of old-school Irish spirit production. “It’s the definition of craft distilling,” Donal says.

At 40% ABV, Glendalough’s Premium Irish doesn’t quite approach the organ-melting potency of homemade poitín. But the recipe is rooted in tradition, dating back to the 1700s. Made from a mash of malted barley and sugar beet and aged in Irish oak barrels, the clear spirit has the body of a single-malt whiskey but a sweet flavor that’s almost reminiscent of rum.

Consumed neat or on the rocks, Glendalough’s poitín has a somewhat creamy mouthfeel with an overall earthiness and a blend of fruits that we don’t encounter often on our side of the Pond, like gooseberries and blackcurrants. It makes for an unusual but appealing tasting experience.

It also works well in cocktails, and Blue Dragon’s Cliffs of Glendalough features a bold, coffee-infused poitín with rich notes of chocolate and spices.

Resurgence of Irish Whiskey

An unfamiliar spirit like poitín might require some explanation, but Irish whiskey needs no introduction. After decades of playing second fiddle to Scottish whisky – in terms of popularity, anyway – Irish whiskey has spent the past several years reclaiming its onetime international glory. 2011 marked the first year that Irish whiskey outsold single malt scotch in the United States, and the spirit’s been on a global upswing since then.

That makes the timing of Glendalough’s entry to the market fortuitous. They offer three whiskies – 7-year and 13-year single malts, and as of this March, an intriguing product called Double Barrel. Hearkening back to a 19th-century style, it’s a single-grain whiskey that spends three and a half years in an American bourbon barrel before being transferred to a Spanish sherry barrel for six months.

Double Barrel

The result is a whiskey with an oaky vanilla flavor and an unexpected fruit character. Donal calls it “light, sweet, and complex,” with depth from malted barley and sweetness from corn. It’s a very accessible whiskey, but surprising notes of spice, ginger, and nutmeg make it complex enough to interest a veteran whiskey drinker.

After sampling it neat, I ordered the Double Barrel in a cocktail, expressing no preference for the type of drink as long as it showcased the whiskey. Our bartender went all out and made “something special” – an Old Fashioned variation with the Glendalough Double Barrel, Benedictine, allspice-infused honey syrup, and old fashioned bitters.

Special indeed! The honey and spice smartly complemented the sweet and spicy notes in the whiskey, while the Benedictine added a bitter, herbal character.

Growth of a Brand

According to the Irish Spirits Association, Ireland exported about 6.2 million cases of whiskey last year, and that figure is projected to double by 2020.

Amid this rapidly increasing global demand, Glendalough Distillery is gradually carving out a small niche for itself. As of March 2015, you’ll only find their spirits in Boston, New York, Atlanta, and Washington, D.C., but the essence of craft distilling is starting small and worrying more about quality than sales figures.

And Glendalough seems content to build their brand not with flashy ad campaigns but by establishing relationships with bar owners, managers, and industry professionals – people who appreciate a small-batch spirit with a unique flavor profile that can feature in an original cocktail.

Irish Hospitality

Some good ol’ Irish charm doesn’t hurt either, as is evident during my conversation with Donal. Chatting with Glendalough’s brand manager is a genuine pleasure. The man has an inexhaustible supply of stories about his native Ireland, the history of Irish distilling, the spirits industry in general, his favorite Boston bars, you name it.

But it’s more than just idle chatter. Entertaining tales and anecdotes aside, Donal’s passion for Glendalough’s spirits is unmistakable, as is his respect for Ireland’s distilling heritage. The Emerald Isle's spirit industry is one of the oldest in the world and has endured staggering swings of fortune, from once having hundreds of distilleries to being nearly wiped out to having all of its major producers bought up by foreign investors.

Donal and company are adding a new chapter to that dramatic narrative.

And while it’s all well and good that huge corporations are bringing Irish whiskey to every corner of the globe, small craft distilleries like Glendalough are getting back to what made the stuff so popular in the first place.

“You can look back on it and say, I made that,” Donal remarks as I admire a bottle of his whiskey.

Call me idealistic, but that seems more satisfying than saying “My company bought the company that made that.”

* * * * * * * * * * * * *

Copyright © Boston BarHopper. All Rights Reserved.

Numbing the Pain of Snowpocalypse With Local Spirits

If you know me at all, even just as an occasional visitor to this space, then you are doubtless familiar with my loathing of winter. My disillusionment with this irksome season probably dates back to the moment my parents decided I was old enough to operate a shovel. In all likelihood, that was the first time I realized that a snowstorm meant more than just an impromptu day off from school, an occasion to be occupied with such leisurely pursuits as snow fort construction and sledding. Suddenly, there was work involved – forced manual labor in harsh conditions. At the time, I certainly didn’t appreciate the gravity of the moment, unaware that it was my indoctrination into a lifetime of arbitrary inconvenience between the months of November and April (give or take a few weeks). That realization came gradually, in the form of sore muscles, untimely falls, white-knuckled car rides, and the abandonment of long-scheduled plans. This year, it’s meant impossible commutes in and out of the city, subzero temperatures, and ice dams forcing water into my dining room.

I tell you this not because I think you need to hear another person complaining about the weather, but because this menace of a winter has become an encumbrance on my weekly posts. Of course I realize, fully, that my having to postpone a couple of bar visits doesn’t exactly qualify as a hardship. But in the face of parking bans and the utter catastrophe that is the MBTA, I’ve been hampered in my efforts to share a tale of barhopping on my preferred schedule of once a week.

It was in the midst of this frustrating, snow-induced torpor that, late one night, I decided to treat myself to a glass of bourbon; specifically, Berkshire Mountain Distillers bourbon, a bottle of which was given to me by my friend and fellow barhopper Kat. I had opened the bottle some time ago and used it in a cocktail or two, but had never tried it on its own.

And let me tell you – it was a revelation. The inviting aroma, the smooth texture, the notes of caramel in the finish; I felt revived.

Now my intention here is not to anoint Berkshire Bourbon as the king of whiskies. I’d call it a good, solid spirit, and a genuine pleasure to drink. But given the circumstances of that particular night, it felt like something more. I wanted no other bourbon than that which I’d just poured into my glass.

The episode also provided some much-needed inspiration. I considered writing a short piece about my experience with Berkshire, but then decided to expand it to include some of the other local spirits I’m fortunate to have in my collection. I’ve long been an advocate of drinking locally, but I think that takes on another layer of significance when the region is affected by something like this brutal stretch of winter weather. If you pour yourself a well-earned drink after a marathon shoveling session or a painful commute, there’s a certain kinship in knowing that the booze in your glass was made just a few miles away, by people who are enduring the same frustrations.

That said, here’s a tribute to three local distilleries that are cranking out top-notch products in and for a state that’s been driven to drink by the 100+ inches of snow we’ve racked up over the past month.

We begin with the inspiration for the post.

Berkshire Mountain Distillers – Bourbon

As the name would imply, Berkshire Mountain Distillers makes its home in Massachusetts’ mountainous Berkshire County. When BMD set up shop in 2007, it did so as the first legal distillery in the Berkshires since Prohibition. Their line of handcrafted spirits has grown to include rum, vodka, and several varieties each of gin and whiskey. A few of their offerings have won awards, and all of them have won praise among discerning drinkers.

Berkshire Bourbon is made with corn grown on a farm near the distillery and aged in American white oak barrels. It isn’t aged terribly long; like any young distillery, BMD is unable to speed up time to produce a 10- or 12-year-old spirit. But if it lacks some of the complexity of an older bourbon, its smoothness, aroma, and flavor more than compensate. It’s an approachable, easy-drinking bourbon with just enough bite and a hint of spice; prominent notes of caramel and vanilla give it an overall sweetness. I’ve found Berkshire Bourbon makes a mean Old Fashioned, but after my winter’s eve epiphany, I’m drinking it neat from now on.

Website:http://berkshiremountaindistillers.com/

* * * * * * * * * * * * *

Bully Boy Distillers – Hub Punch

While Berkshire Mountain Distillers was the first legal distillery to open its doors in the Berkshires since Prohibition, Bully Boy was the first to do so in Boston. And yet, Bully Boy’s roots date back to the days of that so-called Noble Experiment. Bully Boy’s owners, brothers Will and Dave Willis, trace their distilling roots at least as far back as the 1920s, when liquor was quietly available on their family’s farm in Sherborn, Massachusetts. Today their small-batch distilling is entirely legal, and yet there’s an obvious appreciation for history in their ever-expanding product line.

Hub Punch is a most intriguing elixir. Inspired by an 1800s-era recipe associated with a long-shuttered New York hotel, Hub Punch infuses Bully Boy’s barrel-aged rum with a blend of fruits and botanicals. The result is an unusual combination of fruity and bitter components, giving an unexpected herbal bite to a spirit normally known for its sweetness. Consumed neat, it’s drinkable but intense, with a fruit-forward character. It’s excellent in a cocktail, though, and Bully Boy offers a few recipes on their website.

The most traditional partners for Hub Punch are ginger ale and soda water, as with the eponymous “Hub Punch” cocktail. This mix of Hub Punch, ginger ale, soda water, and lemon is a crisp, fruity, refreshing drink with a hint of tartness.

Website:http://www.bullyboydistillers.com/

* * * * * * * * * * * * *

GrandTen Distilling – Fire Puncher Black

Last summer I visited GrandTen Distilling’s historic South Boston facility for an up-close look at small-batch spirit production. While there, I had the pleasure of sampling eight of their nine products. Why not all nine? Because they were out of Fire Puncher Black – a seasonal offering that combines GrandTen’s chipotle vodka with cocoa nibs from Somerville’s Taza Chocolate.

I finally got to try the spirit later that year when GrandTen hosted a bartender battle at its site. As part of the final round of the competition, two contestants were asked to create original cocktails using Fire Puncher Black. And you know, that’s no mean feat. With its complex blend of spicy pepper and dark chocolate, Fire Puncher Black is not exactly the most versatile of spirits.

It’s definitely fascinating to drink on its own. You get chocolate in the aroma, pepper in the first sip, and a finish that’s neither too hot nor too sweet. But if you’re looking to use it in a cocktail, GrandTen offers a few ideas on their website, the most exciting of which is called Joe vs. The Volcano.

Named for a 1990 film starring Tom Hanks and Meg Ryan, this tiki-style drink features tropical flavors, a chocolate base, and a hint of fire. It combines Fire Puncher Black, GrandTen’s Medford Rum, lemon juice, lime juice, pineapple juice, and coconut milk. There’s a lot going on in this one, but it’s ultimately a smooth cocktail that packs a punch. The chocolate really comes through in the finish, even with all those vibrant flavors. And while there’s a bit of chipotle pepper in the final product, the effect isn’t so much about heat as it is warmth.

Website:http://www.grandten.com/

* * * * * * * * * * * * *

Warmth is something we could use right about now, whether it’s in the form of a spicy tiki drink, a fortifying rum cocktail, or a soul-warming tumbler of bourbon. Or, you know…the sun, melting the snow and ice.

On that note, it looks like we might be moving past the worst of the winter, and BBH will be back on a regular schedule soon enough. But I swear, one more snowstorm, and I’m rebranding myself as Florida BarHopper.

* * * * * * * * * * * * *

Copyright © Boston BarHopper. All Rights Reserved.

Good Things Come in Small Batches: A Tour of GrandTen Distilling

For all the fascinating topics that the brand ambassador of a microdistillery could expound upon – the distillation process, the challenges of running a small business, the snazzy vintage pickup truck used to make liquor deliveries – it’s noteworthy how much time GrandTen Distilling’s Lonnie Newburn spends talking about labels.

No, I don’t mean “The GrandTen Label,” as in the line of craft spirits that have won favor among local mixologists and praise from national media. I mean the actual, physical labels on the bottles.

Lonnie points out the text and numbering on each label, signifying batch and bottle numbers. He comments on the style, shape, and length of the labels, even the type of paper used. He hints at images hidden among the floral designs of GrandTen’s line of cordials.

More than anything, Lonnie groans whenever he notices a label that’s askew, however imperceptible it may be to the untrained eye. “That label’s crooked because of me,” he mutters.

To the average person taking a tour of GrandTen’s South Boston facility, label design and placement might not be the most exhilarating subject of the day. But when you’re one of four individuals responsible for ushering a completely handmade spirit from still to bottle to shelf, details like that are important.

And if they obsess that much about the adhesive affixed to the bottle, you can imagine how much care goes into the product behind it.

Birth of a Boston Distillery

One of only two distilleries in the city of Boston, GrandTen Distilling has its roots in a business plan that Matthew Nuernberger, the distillery’s co-owner and president, wrote for his MBA program at Babson College. Upon graduating, he teamed up with his cousin, fellow co-owner and head distiller Spencer McMinn, who had earned a PhD in chemistry from the University of Virginia.

Armed with business savvy and scientific know-how, they acquired space in Southie in 2010 and set about creating small-batch spirits for a savvy drinking public with a growing appreciation for craft cocktails and quality ingredients.

After clearing the innumerable regulatory and licensing hurdles that all would-be distillers must face if they want their product to be considered something other than moonshine in the eyes of the law, in April 2012 the cousins finally unveiled their first spirit – an American gin.

Less than three years later, GrandTen has emerged as one of the most respected regional players in a fast-growing craft spirit movement.

They’re certainly one of the most visible. It’s not difficult to spot GrandTen doing business around town, considering their distinctive mode of transportation – a 1966 Ford F-100 pickup truck, custom-painted “Steve McQueen Green” and sporting the GTD logo.

Finding the spirits isn’t hard, either. Today there are nine original GrandTen products, which appear on the shelves of more than 300 Massachusetts bars, restaurants, and liquor stores. Distribution has expanded to Connecticut, Rhode Island, and Pennsylvania (and, oddly enough, Washington state), and when I toured the distillery a few weeks ago, they were readying their first international shipment.

Not bad for a company that only recently hired its fourth full-time employee.

Historic Location

While GrandTen is still a young company, the nondescript Andrew Square facility out of which it operates has deep local roots and a colorful history. It was built as an iron foundry in the early 19th century by renowned metallurgist Cyrus Alger. The foundry supplied munitions to the U.S. government, including cannon balls used during the War of 1812.

Later, the foundry’s focus shifted from weapons to wire production, and then lived a long life as a series of machine shops, small production companies, and automotive repair facilities.

When GrandTen took over the old foundry, it had fallen into disrepair and was in need of extensive renovation. Remarkably, some of the original structure remains – its rafters and wooden support beams have weathered the passage of time and imbue the space with a sense of tradition and longevity.

But despite the building’s historical aura, the distillery looks pretty much like your average industrial warehouse – plastic buckets and hoses strewn across a concrete floor, tools lying on tables, piles of cardboard boxes and packing materials, brooms leaning against walls.

Meet Adrian

Of course, most warehouses don’t have a 50-gallon copper still in the back. The Adolf-Adrian Brennereianlagen still, which Lonnie affectionately refers to as “Adrian,” is believed to be one of only five of its kind in the United States.

“Adrian is a very unique eau de vie or brandy still,” Lonnie explains. “He was born at the Adolf-Adrian Distillery Manufacturers in Germany. They used to be a copper works, and have been producing handmade copper stills since 1811. They are very low-volume and produce a limited number of stills a year – fewer than 10 – and most stay in Europe.”

With its spherical dome, various portholes, and a tall distillation column that looks like an upraised arm, Adrian vaguely resembles a killer robot from a 1950s sci-fi movie. But Adrian only does good deeds – nearly every day, he’s busy heating, cooling, and infusing the liquids that will become GrandTen’s next batch of spirits, from their flagship gin to more experimental items. Next to Adrian is a 1,000 gallon fermenter, and a storage tank beyond that.

All throughout the distilling area is evidence of the copper still’s output – oak barrels that have recently been hammered shut, pallets of whiskey ready to be shipped, bottles of gin awaiting labels.

The sweet aroma of molasses used in GrandTen’s new rum permeates the entire room, and on the floor is a large pile of chipotle peppers that had been infusing a batch of spicy vodka earlier that day. The peppers are locally grown, as are nearly all of the ingredients GTD uses – yeast for the rum comes from the Trillium brewery in Fort Point, and botanicals deployed in the gin are purchased from Christina’s, a spice shop in Cambridge’s Inman Square.

As Lonnie explains, it’s an approach that benefits the spirits as well as the community. “Using local products certainly brings a better flavor to the end spirits, keeps more money in Massachusetts, and ensures freshness,” he says.

The tour moves from the production area to the distillery’s front room, where dozens of spirits are aging in barrels. GrandTen barrel-ages six of its products – a not insignificant investment of time and resources for a small distillery.

Brandy in the Works

Some of those barrels hold GrandTen’s forthcoming tenth product – an apple brandy, which Lonnie calls “a true New England classic.” The brandy will stay in the barrels for at least another year, but judging by Lonnie’s enthusiasm, it will be worth the wait.

“We crushed thousands of pounds of red New England apples, fermented them on the skin, and distilled a truly delicious, creamy, caramel, and effervescent red apple brandy that has been aging for over 2 years now,” he says.

But there’s no need to wait for GrandTen’s other spirits, and after learning how they’re made, it’s time to find out how they taste. Much like the facility as a whole, the tasting area is a functional, bare-bones affair.

There’s a roughly cut concrete bar, behind which are shelves lined with bottles of GrandTen and a few mixers. Two large wooden tables are fairly recent additions to the tasting room, handmade by the GrandTen crew to get visitors more involved in the tasting process.

Visitors should get comfortable, too, because there’s plenty to sample.

Wire Works Gin

The tasting begins with Wire Works American Gin, the name of which is a nod to the foundry’s previous life as a wire works. American gins tend to be less strict than traditional London dry gins in their use of botanicals. While all gins must use juniper, which contributes the spirit’s distinctive pine flavor, Wire Works dials back that herbal pungency in its botanical blend.

The result is a clean, balanced, highly drinkable gin, with notes of white pepper, citrus, and Angelica root. The botanical recipe is secret, of course, but Lonnie reveals one of the more unusual ingredients – cranberries, which don’t impart flavor but add acidity and contribute to mouthfeel.

Wire Works Special Reserve

The Wire Works Special Reserve that Lonnie opens next was bottled that very day. It’s the exact same gin as the Wire Works, except it spends a year aging in American oak bourbon barrels. The barrel aging accounts for the gin’s darker complexion and, more importantly, its whiskey-like complexity. It’s a warmer spirit with a bit of spice in the nose and soft notes of vanilla at the end.

The Special Reserve is similar to an “Old Tom” style of gin, so it works well in a Martinez, but can just as easily substitute for whiskey in cocktails.

South Boston Irish Whiskey

Speaking of whiskey, the South Boston Irish Whiskey is the only GrandTen product that isn’t made entirely on the premises. The whiskey is fermented in Ireland and shipped to the South Boston distillery, where it’s blended, aged in bourbon barrels, and bottled.

The whiskey arrives from the Emerald Isle in a fairly raw state, often with pieces of wood and charred oak floating in it. The wood chunks get strained out, of course, but the oaky essence remains, combining with sweet cinnamon spice and notes of banana.

Medford Rum

Medford Rum may be GrandTen’s newest offering, but it’s been hanging around the distillery longer than any other spirit. Aged for two years in charred American oak barrels, the Medford Rum is what Lonnie calls an “old, tavern-style rum.” It hearkens back to the colonial era, when Massachusetts was home to upwards of 30 rum distilleries.

Rums made in Medford were especially renowned for their superior quality, and the term “Medford rum” became a general way to refer to any dark, full-flavored rum.

The last of those classic rum distilleries closed before Prohibition, but GrandTen picks up the trail with this updated version. Made with blackstrap molasses, the dark, thick liquid that remains after sugar has been boiled out of raw cane syrup, it’s noticeably less sweet than typical rums. With clear notes of butterscotch on the nose and rich caramel flavors, this is a smooth, complex rum that recalls the flavor of a Werther’s Original candy.

Without exaggeration, this is unlike any rum I’ve ever tried, a fact Lonnie attributes to the choice of local products. “Trillium provides us with a blend of New England yeasts that give the rum a regional character that simply cannot be reproduced with commercially available yeast strains,” he says.

Cordials

The rum seems like a tough act to follow, and I’m not sure what to expect as we move into GrandTen’s line of cordials. Cloying sweetness? Herbal intensity? Names like “Amandine” and “Angelica” offer scant clues about the character of the liqueurs, and the label on one bottle appears to be marred by an inexcusable typo.

Amandine

But one sip of the Amandine immediately alleviates my concern. This barrel-aged almond liqueur recently drew praise from the Wall Street Journal, which lauded GrandTen’s “less-is-more approach to Amaretto.” With a pure, full-flavored almond character and a unique mouthfeel, the Amandine recalls the softness and warmth of a homemade almond biscuit.

Angelica

The Angelica, meanwhile, utterly defies categorization. Described as a “botanical liqueur,” the name derives from the spirit’s primary ingredient – Angelica root, a tan-colored herb with a sweet, earthy flavor and hints of anise.

The eponymous herb is used to great effect in the cordial, combining with notes of cinnamon, clove, and juniper for an entirely unique liqueur. It would be like St. Germain and chartreuse having a kid; the Angelica lacks the brightness of St. Germain and the bitterness of chartreuse, but maintains an aromatic, floral essence and a fragrant bouquet of spices.

Craneberry

All throughout the tasting, I kept glancing at the third cordial – Craneberry – and wondered how a distillery that consistently demonstrates such painstaking attention to detail could have flubbed the spelling of “cranberry” and allowed the error to remain on the label.

But the extra vowel isn’t an oversight – “craneberry” is the word that early Massachusetts settlers used to refer to the cranberry flower, which resembles a crane. Here it’s a rum-based liquor infused with Cape Cod cranberries and aged with citrus in cabernet barrels. Like the Amandine and Angelica, the Craneberry is full-flavored but not overly sweet. A seasonal release, this is a holiday cocktail waiting to happen.

Fire Puncher Vodka

The tasting closes with one of GrandTen’s standard offerings – and another history lesson. Fire Puncher vodka was the distillery’s second product, and with its spicy bite, represents a thumbing of the nose at the preponderance of soft, fruity vodkas on the market. Each batch is distilled with 10 pounds of those fresh chipotle peppers, and Lonnie again credits the local ingredients with imparting such a unique flavor to the spirit.

“The chipotle peppers from Bars Farm [in Deerfield] are of a much higher quality,” he says. “Most chipotle peppers are made from a lower-grade jalapeno because they are going to be smoked; however, our chipotles are made from superior local jalapenos.”

And while the label warns that the spirit is “not for the faint of heart,” the final product is much more about flavor than heat. The vodka has a big, pure pepper essence, and the heat stays on your lips instead of setting your esophagus aflame. Hickory smoke, which is bubbled through the vodka before bottling, rounds out the flavor and makes for a smooth, warm spirit that seems destined for a bloody mary.

The name “Fire Puncher” is inspired by an incident from the distillery’s illustrious past. A fire broke out in the foundry one night in January 1887, and before the fire department could arrive, a concerned chap by the name of Tommy Maguire took it upon himself to climb up to the roof and fight the blaze – with his fists. His efforts, however well intentioned, earned him a ride in the paddy wagon.

Sadly missing from our tasting is Fire Puncher Black, a variation of the chipotle vodka made in collaboration with Taza Chocolate of Somerville. The combination of dark chocolate and spicy pepper sounds divine, but the stores are depleted (don't fret – it'll be back). And while it was only intended to be a limited-edition product, its absence highlights one of the challenges inherent in small-batch distilling – when a spirit runs out, sometimes it’s really, truly gone.

Life in a Small Distillery

Such are the facts of life for a distillery of this size and tenure. Capacity limitations and the inflexibility of the aging process directly influence GrandTen’s product line, even more than they would for a larger, older outfit. Regardless of the volume of spirit GrandTen can produce, there’s only so much space to store it.

And products that require barrel aging can’t be hurried along. If GrandTen ever has designs on releasing an original, 12-year-old whiskey, they need to get the spirit in barrels spirit today if they want it on shelves by 2026. Even now, an unexpected spike in demand can disrupt production schedules or, in the case of the barrel-aged spirits, lead to a gap in availability.

But while GrandTen’s output is restricted by time and infrastructure, their freedom to experiment with handpicked ingredients and design original, innovative recipes is limited only by their collective imagination.

Unlike industry titans, GrandTen isn’t tethered to age-old recipes or methods. Someone operating a still at Beefeater doesn’t have license to throw a handful of cranberries into the botanical mix to see how it might alter the gin’s flavor. But at a microdistillery, an idea like that has the potential to become a signature product.

GrandTen’s facility might look a bit like a garage, but it functions more like a workshop. It’s a creative environment in which energy and ingenuity thrive, risks can pay off, and even missteps have value. The result of that combination of artistry and grunt work is a line of unique, homegrown spirits for a city that’s come to appreciate quality and recognize nuance in its cocktails.

Every night we crowd into places like Backbar and Wink & Nod and wait for original, well-executed drinks made with the best ingredients by the most talented mixologists. It follows that we should seek out the same passion, patience, and devotion to craft in our spirits.

And if you find those qualities in a bottle with a crooked label, well…just consider it a personal touch.

Address: 383 Dorchester Avenue, Boston

Website: http://www.grandten.com/

* * * * * * * * * * * * *

Copyright © Boston BarHopper. All Rights Reserved.

Brugal – Rum Redefined

For a rum that’s been around for 125 years, Brugal keeps a relatively low profile. There’s no swashbuckling ad campaign. No pirates. No glossy posters showing bikini-clad models doing shots of rum on the beach. But being the life of the party isn’t Brugal’s goal. The Dominican distiller has a far loftier mission: changing the way we think about – and drink – rum.

Such is the theme of Brugal’s “Rum Redefined” campaign, which rolled into Boston for three nights this past week and transformed the South End’s Cyclorama into something reminiscent of a distillery visitors’ center. Guests had a chance to learn about Brugal’s unique distillation process, sample three varieties of rum, and get a hands-on lesson in rum-based mixology.

If Brugal is outwardly distinct from other distillers in that it eschews the image of rum as an island-themed party spirit, the difference in the product itself is far more profound. As a molasses-based liquor, rum is known for its inherent sweetness. Many of the cocktails it features in are likewise sweet and tend to be made with a multitude of fruit juices. Brugal’s rums, by contrast, are uncommonly dry.

“People don’t think of drinking rum straight,” says Brian, one of the Brugal reps at the event. “We’re trying to show folks that rum isn’t something you need to cover up.”

His point is well taken – most rums aren’t made for sipping. “The difference is the way we distill our product, Brian explains. “In distillation, we remove a lot of the heavy alcohols, the banana and coconut flavors.”

But the aging process is where the real magic happens. All of Brugal’s rums are aged in white American oak casks. And Brugal takes its cask aging pretty seriously. “We use the same wood policy as the finest single malt scotch,” Brian tells me.

But while the wood policy may the same, the wood itself behaves very differently in the Dominican Republic than it does in chilly Scotland. The heat and humidity of the Dominican climate accelerate the rum’s maturation rate, meaning you don’t have to wait quite so long for the spirit’s rich character to develop. The downside of the warm weather is that Brugal loses 9% to 12% of its annual yield to evaporation. This disappearing act is charmingly known as the “angel’s share,” but angels clearly have a taste for rum – their portion translates to a staggering 25,000 barrels’ worth of lost rum every year.

But those exacting standards and devotion to aging result in a series of exceptional rums that are clean, dry, and surprisingly complex. The amber-hued Brugal Añejo has unexpected hints of caramel and chocolate.

The masterful Brugal 1888 is the first rum to be aged in two different casks – six to eight years in a whiskey cask, two to four more in a sherry cask. With a heavenly aroma and notes of toffee and licorice, it’s the sort of rum that calls for a cigar. My friend Mike, who joined me for the event, put it best: “If I brought this to a whiskey tasting, no one would guess it was rum.”

But the star of the night was Brugal’s Extra Dry offering. This triple-distilled rum is crisp, subtly fragrant, and of course, dry. And it’s still an aged rum, despite its clear complexion; charcoal filtering removes the dark color imparted by the aging process.

Like the Añejo and the 1888, the Extra Dry is good enough to drink neat or on the rocks. But its flavor profile makes it an especially intriguing choice for cocktails. “It’s versatile,” Brian says. “The Extra Dry plays well in a clean, simple cocktail, but one that you can experiment with, too.” So after sampling a few styles, our mixology lesson began, with bartenders from Eastern Standard and Lolita showing us the finer points of mixing Brugal into one of the simplest and most traditional of rum cocktails – the daiquiri.

The daiquiri is a Caribbean classic that’s been unfairly maligned over the years, victimized by artificially flavored sweeteners, mixers, and juices. Frozen daiquiris are fun by the pool, of course, but they aren’t what you’d consider a serious drink. So our cocktail-making session returned the daiquiri to its most basic, refreshing roots – rum, syrup, and fresh lime juice. That last ingredient is especially critical; the dryness and subtle profile of the Brugal accentuates the flavors of the mixers, so using fresh lime results in a naturally sweet, uncluttered cocktail.

After learning about the merits of a traditional daiquiri, we were encouraged us to branch out a bit. With various garnishes and syrups at our disposal, my friend Mike whipped up a sweet, herbal daiquiri with honey and basil.

But the pros still do it best, and the highlight of the night for me was this strawberry daiquiri with jalepeño. Along with the fresh, natural strawberry flavor was a subtle undercurrent of heat from the jalepeño, which made for a pleasant, lip-tingling finish.

Again, it’s the dryness of the Brugal that enables the other ingredients to shine. That hint of heat, and its interplay with the strawberry, is exactly the sort of nuance that would be overpowered by a sweeter rum with its own heavier flavors.

While historically one of the top selling rums in the Caribbean, Brugal has never enjoyed widespread popularity in the United States. That’s changing, though, as mixologists experiment with different brands for an American public that increasingly appreciates complexity in its cocktails. This is the market that Brugal envisions capturing with its Extra Dry variety.

The white rum represents a departure from Brugal’s other styles, but not from its standards. “They want to leave a legacy that, 125 years from now, they can still be proud of,” Brian tells me. A devotion to quality doesn’t always translate to longevity. But for Brugal, it’s a formula that’s worked pretty well since 1888.

* * * * * * * * * * * * *

Copyright © Boston BarHopper. All Rights Reserved.

Smoky Cocktails With The Black Grouse

Scotch has never been the most approachable of liquors. Like all whiskies, it’s an acquired taste; and while it’s certainly one worth acquiring, there are rules to heed before you even think about pouring yourself a glass. Some varieties are best enjoyed on the rocks; others must be consumed neat. A little water might open up the flavors of certain scotches – and completely ruin others. Ultimately it’s all a matter of personal preference, but scotch connoisseurs tend to be passionate – and vocal – about their customs. So if the simple act of dropping an ice cube into a glass of scotch can provoke outrage, mixing scotch into a cocktail must be on par with a capital offense, right?

Not according to the good folks at The Famous Grouse. And with more than a century’s worth of distilling experience, they’re free to keep their own counsel on the matter.

The Famous Grouse has been making blended whisky in Scotland since 1897. The smoothness, drinkability, and affordability of its flagship product have made The Famous Grouse the best-selling scotch in the land of kilts and bagpipes. But a newer addition to the Grouse’s line has rightfully earned its share of the spotlight.

The Black Grouse differs from the original blend in that it’s made with peat, which gives many scotches their signature smoky character. It’s a smooth, aromatic scotch with a long, oaky finish. The Black Grouse is exquisite on its own, and its makers do recommend consuming it neat. But they’re not terribly preachy about the best way to enjoy their scotch, even going so far as to offer cocktail recipes on their website. Of course, you wouldn’t expect pretension from a brand that named itself after a Scottish game bird similar in appearance to a chicken.

That said, the Black Grouse flew into Boston this week and teamed up with mixologists at two bars to see how its smoky scotch fared in a range of cocktails. I was fortunate to be part of a small group that took part in a scotch-themed mini bar crawl that was as enlightening as it was intoxicating.

The dark, elegant confines of the backroom bar at Carrie Nation provided an appropriately dignified atmosphere for the first two cocktails of the evening. Bartender Brian Kline explained that his first concoction, the Sweet Release, was modeled after a 1930s-era cocktail called the Remember the Maine. Combining Black Grouse, sweet vermouth, Luxardo cherry juice, Angostura bitters, and an absinthe rinse, the Sweet Release was strong, smoky, and tart. Brian noted that the cherry juice served to bring out the smokiness of the scotch, while the absinthe gave the drink a pleasantly bitter finish.

“Part of what I love about this job is coming up with drinks with ingredients that people think they don’t like,” Brian said in his introduction to the evening’s second cocktail, the Ginger Kiss. "You'll like this," he added. Made with Black Grouse, yellow chartreuse, fresh lemon juice, and ginger liqueur, plenty about this could challenge the palate of a timid drinker. But the Ginger Kiss was a vibrant, well-balanced cocktail with a smoky essence and notes of citrus. The distinctive flavor of ginger permeated the drink without overpowering it, and the chartreuse was used sparingly.

Thankfully there was some food, too, which kept us all upright while we sipped our potent libations. Hearty pulled pork sliders were a good match for the smoky notes of the Sweet Release.

Peanut Thai chicken skewers were highly addictive and paired well with the sweetness of the Ginger Kiss.

From there we headed to the cave-like, downstairs bar at Stoddard’s, where mixologist Tony Iamunno offered his take on how to employ scotch in a cocktail.

First up was Someone Else’s Girl, the name of which, Tony wistfully noted, was autobiographical. This decadent drink was a mix of Black Grouse, egg white, Crème Yvette, raspberry syrup, lemon juice, and Angostura bitters. Garnished with raspberries, this cocktail was nothing short of luxurious. The egg white gave it a creamy texture, while the Crème Yvette, a fruity, violet liqueur that reemerged in 2009 after a 40-year hiatus, provided a well-rounded sweetness. Using a smoky scotch like Black Grouse in such a sweet, velvety drink was clever and unexpected.

Coming on the heels of that soft, creamy cocktail, the final drink of the night was like a bacchanal of bitterness. The Smoky Glasgow combined Black Grouse, absinthe, and dry vermouth in a well-conceived but intense cocktail. This was a serious drinker’s drink, with a prominent licorice flavor from the absinthe and an herbal dryness from the vermouth. Both of the bitter liquors served to enhance the smoky character of the Black Grouse, and an orange peel offered just the slightest hint of citrus. A challenging combination of flavors, but well done.

All that bitterness was balanced by a plate of Stoddard’s’ chipotle citrus chicken wings, which brought some spice and a little sweetness to the party.

And as a special treat, we got an order of that timeless staple of French-Canadian cuisine, poutine. These hand-cut fries topped with melted cheese curds and a delicious duck fat gravy went well with both cocktails. Then again, poutine goes well with just about anything.

As it turns out, scotch goes well with a few things too. While there are, of course, a handful of traditional scotch-based cocktails, they have yet to enjoy a resurgence in popularity; it’s rare that I hear someone order a scotch and soda or a Rob Roy. But the drinks Brian and Tony made for us this week demonstrated an impressive range of styles for scotch drinks, from classic to indulgent to vigorously bitter.

For those of us who typically wouldn’t pair scotch with anything other than a quality cigar, the experience illustrated the benefits of experimenting with this most distinguished of liquors. Granted, making a whisky sour with an 18-year-old Macallan would be considered an alcoholic atrocity, but using a more versatile scotch like The Black Grouse in a high-end cocktail is unlikely to invite scorn. A glass of scotch served neat may forever be the pinnacle of respectability in the world of booze, but even the most stubborn whisky drinkers know when to bend the rules.

* * * * * * * * * * * * *

Copyright © Boston BarHopper. All Rights Reserved.

Downeast Cider House

I cannot precisely recall the first time I tried apple cider, but I’m almost certain it was at a Thanksgiving dinner when I was a kid. For my family, cider was a turkey day staple, complementing the food on our table while reflecting all the wonderful flavors of autumn in New England.

The first time I tried hard cider? That I remember vividly – and not a little bit fondly.

Sometime in the late 1990s, I was introduced to Cider Jack, which at the time was one of few commercial hard ciders widely available in the United States. As a beer drinker, I was no fan of “malternatives.” But I figured, hey, it’s cider, right? How bad could it be?

Turns out, it could be pretty bad.

Cider Jack was a scratchy, artificially flavored, sharply carbonated beverage that bore scant resemblance to the thick, fresh juice that heralded the holiday season. You know how leaving the cap off a bottle of apple juice for a week or so will supposedly cause it to ferment? I imagine the result would taste something like the now defunct Cider Jack.

If there was one benefit to Cider Jack’s inexplicable popularity, it was that it helped open the door for other – and much better – hard ciders. Eventually my harsh opinion mellowed a bit; I learned to appreciate an occasional Magners and later developed a genuine fondness for Harpoon’s cider, which at least tasted like actual apples had made an appearance in the brewing process. But I never loved it, and I resigned myself to the depressing reality that the chasm between non-alcoholic apple cider and industrial hard cider would never be bridged.

And then, on a summer night in 2012, something happened that forever altered my understanding of hard cider.

I was enjoying drinks in Cambridge’s Central Square with a few fellow barhoppers, and when it came time to change locations, my friend Jen lobbied for a trip to Kendall Square’s Meadhall. Her reason? They had a cider on draft that she really liked. Now as much as I enjoy Meadhall, it hadn’t really been on that evening’s agenda; and going there specifically for a hard cider was hardly incentive. But Jen was persistent, so we headed to Kendall. Upon arriving at Meadhall, Jen ordered her precious drink – something called Downeast Cider – and offered me a sip of the much-ballyhooed beverage.

And that, dear readers, is when I first fell in love with hard cider.

If there was one obvious distinction between Downeast and every other hard cider I’d tried, it was this – Downeast resembled actual apple cider. As in, the stuff I always drank in November (but with alcohol!). Not too sweet, not overly carbonated, and – unlike every other hard cider on the market – not filtered. Whereas you could read a newspaper through a glass of most hard ciders, this unfiltered brew had a cloudy complexion, more akin to that of genuine cider – not to mention a rich, natural flavor.

After that I became something of a Downeast evangelist, talking it up to anyone who would listen and dragging people to Meadhall to try it. Not that Downeast needed my help – their cult following was quickly growing into a regional phenomenon. More bars began offering it on draft, and eventually a canned version appeared on store shelves. In February 2013, Downeast co-founders Tyler Mosher and Ross Brockman moved their operation from Leominster to Charlestown; last December, they hosted a big launch party to officially christen their Downeast Cider House and formally announce their Boston presence. And just this past month, Tyler and Ross were included on Forbes' annual “30 under 30” list. Not bad for a couple of Bates College grads with no prior brewing experience.

A few days before their launch party, I met with Tyler for a tour of the new digs and an education on all things cider.

While Downeast is the sexy choice among ciders these days, the place where the magic happens is more functional than fashionable. The Downeast Cider House, which sits in the shadow of the Tobin Bridge, is a large industrial space filled with brewing tanks, canning equipment, kegs waiting to be filled, and cases of cider ready to be shipped.

The gray, concrete floor is strewn with hoses; electrical cables hang from steel beams on the ceiling; puddles of water await a mop. The only splash of color comes from a huge apple tree painted on the back wall.

A few tables constitute a makeshift office, and that’s where Tyler, Ross, and Ross’s brother Matt deal with the business of making, selling, and distributing cider. And while those matters take up increasing amounts of their time, Tyler and Ross’s typical day is still consumed with making their cider – including the drudgery of cleaning tanks and canning their product. It’s an honest, elbow-grease approach that isn’t too far removed from their earliest days of brewing cider in the basement of their college dorm.

The Downeast story begins in Maine. Tyler and Ross became friends while attending Bates and discussed the notion of starting a business together someday. Cider wasn’t in their plans yet, but after a few overseas trips, they noticed the popularity of hard cider in other countries; the U.S. market was comparatively dry. Another thing they noticed? That most hard cider was “cider” in name only. “It was a real bummer,” Tyler says, “not finding any ciders that were made from freshly pressed apples.”

So when they graduated, they started putting their plans into action. A complete lack of cider-making experience might have given other would-be brewers pause, but Tyler and Ross were undaunted. “We were in college, and we were young and cocky,” Tyler admits with a laugh. But they had a friend whose family owned an apple orchard and an apple press, so that helped. And after eight months of trial and error, they also had a recipe. Before long, the two cider-making novices would be bringing their new product to market. “We had this blind confidence,” Tyler says. “We didn’t know how hard it could be.” They would soon find out.

Downeast set up shop in Waterville, Maine, and began distributing their cider on a relatively small scale. As Tyler recounts, “We made a few kegs, sold them locally, and thought ‘Wow, this is sweet – making and selling our own cider!’” Then a sales trip to Massachusetts resulted in five new accounts – and their first professional crisis. “We got four times the order that we were expecting. We didn’t have enough kegs, didn’t have enough cider.” It didn’t help that it was a bad year for apples, and their supplier ran out.

That led to some tough decisions. Fill the order with an inferior product? Call their new customers back and say “uh, sorry, we’re out of cider”? Of course not. Tyler and Ross ultimately managed to find a new supplier, but it meant moving their home base to Leominster, Massachusetts. Their departure from Maine may have been unceremonious, but it was clear, even then, that the pair were unwilling to compromise the integrity of their product. That “no shortcuts” philosophy remains central to their current vision – and the outcome is a consistently enjoyable craft hard cider.

As we toured the facility, Tyler expounded on what distinguishes Downeast from so many other brands. The cider is made with locally grown, freshly pressed apples – a blend of Red Delicious, McIntosh, Cortland, and Gala. The velvety consistency comes from the type of yeast. “Ale yeast gives it that smoothness,” he explains. “Most ciders use champagne or white wine yeast.” Tannins, known more commonly for their use in wine, provide mouthfeel and body. (In an episode I won’t soon forget, Tyler encouraged me try some dry tannins – which taste roughly like cigarette ash. Apparently something good happens once they make it into the brew. Gentleman that he is, Tyler also submitted to tasting the tannins to share in my misery.)

But if there’s one thing that people immediately notice about Downeast, it’s that the cider is unfiltered. Compared to most commercial hard ciders, Downeast has a darker, richer complexion. “It’s hard to do,” Tyler admits. “When we started, everyone told us we had to filter it.” But filtering affects more than just the cider’s appearance. “We tried a filtered version, but it just stripped all the taste away. We said, ‘we can’t do this to our cider.’”

The process may be more complicated, but the result is a cider with a full-bodied flavor and smooth texture, free of concentrated juices and artificial sweeteners. Other ciders literally pale by comparison.

My tour of the Cider House is illuminating, and not just because of the glimpse at how cider is made. Seeing a business that’s still evolving is just as fascinating. Clearly visible are the vestiges of a young company accustomed to operating on a shoestring budget. There’s the Chinese-made canner Tyler and Ross bought because it was cheap; it didn’t work and they ended up having to buy another one. There’s the pasteurizer that they built themselves, because commercial ones are so expensive.

Tyler still seems astonished by the cost of kegs. And the Downeast workforce is little more than a skeleton crew; aside from Tyler, Ross, and Matt, there are two sales reps and a couple of guys who help with the packing and kegging.

It’s a small operation, but it’s easy to see that bigger things are on the way. Their cider is in ever-increasing demand, and their product line is expanding. Downeast already offers a cranberry cider, an alternative to their original blend. A bit more risky are a couple of non-cider products slated to hit the shelves this year. Tyler seems a tad uncertain about how customers will react to Downeast branching out – a far cry from the “blind confidence” that fueled his and Ross’s earlier ambitions. I’d say there’s little cause for concern; as long as they maintain their dedication to quality and a “no shortcuts” mantra, it’s hard to imagine any of Downeast’s offerings falling flat.

But Downeast’s expansion plans are unlikely to distract Tyler and Ross from their flagship product. And that’s a good thing, because their success is bound to spawn imitators. You can be sure that the market is well aware of Downeast’s popularity, and it’s only a matter of time before an upstart brewery – or even one of the big guys – comes out with their own unfiltered craft cider. It’s a likelihood Tyler is well aware of. “The only way to avoid competition hindering our business is to stay ahead of it.”

I’d say they’ve got a pretty good head start.

******

If you’re a Downeast devotee and are looking to visit the command center, be patient – the Downeast Cider House isn’t officially open for tours yet. That will be changing, though, possibly as soon as next month. In the meantime, to learn more about the cider, check out the website. You’ll find plenty of amusing stories about Tyler, Ross, and the whole Downeast crew. They even offer cider-based cocktail recipes; I found the recipe for “Downeast on the Rocks” particularly compelling.

Website:http://www.downeastcider.com/

* * * * * * * * * * * * *

Copyright © Boston BarHopper. All Rights Reserved.

An Evening With Montelobos Mezcal...and the Three Amigos

The year is 1916. The rural village of Santo Poco, Mexico, is being extorted by a cruel bandit and his obsequious cohorts. The people of the village have long since abandoned hope and resigned themselves to their plight. But when one of the villagers, a young woman named Carmen, sees a silent film depicting the exploits of three wealthy Spanish landowners who fight for justice and the good of the common man, she hatches a desperate plot to save Santo Poco. Unaware that the on-screen heroes are merely actors, not true crusaders, Carmen dispatches a telegram requesting their help and promising a handsome reward. The telegram reaches the actors, who have recently been fired by their studio over a salary dispute. Interpreting the telegram as an invitation to stage a performance, the three eagerly accept and head to Santo Poco – not realizing they are walking into a real-life battle with a group of ruthless thugs led by the notorious outlaw El Guapo.

This, my friends, is the premise for that enduring classic of 1980s cinema, the ¡Three Amigos!, a film I was fortunate to become reacquainted with last week when Cambridge’s Moksa screened it as part of a promotional event for Montelobos Mezcal. And while it would be difficult to upstage the hijinks and heroics of Lucky Day (Steve Martin), Dusty Bottoms (Chevy Chase), and Ned Nederlander (Martin Short), the true stars of the evening were bartenders Curtis McMillan, Brian Mantz, and Tyler Wolters.

First, a few words about mezcal. Just as the Amigos are wrongly perceived as valiant crusaders, mezcal often suffers from a case of mistaken identity. Many people think the spirit is a type of tequila, when in fact, tequila is a type of mezcal. True, both are made in Mexico and originate from the agave plant, but the similarities end there. For starters, they are largely produced in different regions of Mexico. And tequila, by law, is made solely from the blue agave plant, while mezcal can be made from a plethora of agave plants.

But the most obvious difference between the two spirits is the flavor profile. Mezcal is famous – or infamous – for its distinctive smoky essence. This comes from roasting the piña, which is the heart of the agave plant. The traditional production method involves roasting the piñas in an underground pit lined with volcanic rock and wood, covered with earth and logs. The piñas get smoked over the course of a few days before being mashed, fermented, and distilled. It’s a process that has been industrialized over the years, but smaller, craft distilleries, like Montelobos, have returned to this time-honored, handcrafted approach.

The result is a spirit that nicely balances bitter and sweet flavors, with notes of vanilla, pepper, agave, even citrus. The signature smoky essence is milder and more natural than I’ve encountered in other mezcals; not harsh or overpowering.

Although mezcal is typically consumed neat in Mexico, mixed drinks were the order of the night at Moksa. Each of the three featured cocktails, with names inspired by the evening’s film, was designed by one of the sombrero- and poncho-clad amigos working behind the bar.

First up was “Son of a Motherless Goat,” made by Moksa’s bar manager, Tyler Wolters. This mix of Montelobos, Byrrh (a quinine-flavored, fortified wine), Montenegro, maraschino liqueur, and coffee bitters, finished with a twist of orange, was like a spicy, smoky Manhattan. The coffee bitters added a subtle anise flavor, while the orange peel contributed some bitterness and citrus notes.

Brian Mantz is the bar manager at Carrie Nation, and his “Plethora of Piñatas” combined Montelobos, Lillet Blanc, a grapefruit cordial, and lime. Light and refreshing, it was like a lemonade with a subtle, smoky bite.

As Vice President at the Boston chapter of the United States Bartending Guild, you could say Curtis McMillan knows a thing or two about cocktails. This whole event, incidentally, was his brainchild, part of the local launch for Montelobos. Curtis’s “Invisible Swordsman” cocktail may have been the most complex of the night, with Montelobos, Cherry Heering, Solerno blood orange liqueur, grapefruit, agave, and allspice. Despite combining so many boldly flavored ingredients, it was well balanced, with a big sweetness up front.

While the hombres behind the bar whipped up some potent bebidas, the rest of us watched the tense drama unfold on screen. When the Three Amigos ride into Santo Poco, the villagers aren’t sure what to make of their flashy, would-be saviors. But the trio is lionized after an apparent victory over El Guapo’s bemused minions, and a night-long fiesta ensues. The celebration is short-lived, however, and so is the villagers’ adulation. El Guapo himself arrives the next day; unmoved by the Amigos’ histrionics, he exposes the heroes as frauds, sacks Santo Poco, and kidnaps the beautiful Carmen.